GLOBAL TRENDS SHOW WHALE SHARK POPULATIONS ARE DECLINING

The global population of whale sharks has declined by more than 50% in the last three generations. This decline occurred alongside targeted fisheries operating in the Indo-Pacific region. These findings led to the up-listing of the species to Endangered under the IUCN Red List in 2016.

Without proper conservation measures, these gentle animals remain highly threatened and face an uncertain future.

Threats to the species

Targeted hunting and accidental catch

Vessel strikes (commercial and recreational vessel)

Unsustainable tourism

Climate change (shift and reduction in food distribution/availability)

Habitat degradation and destruction (Oil & gas extraction, transportation and processing, coastal development, solid and chemical pollution)

Overfishing and depletion of food

WHALE SHARKS IN THE PHILIPPINES

Whale sharks were targeted by fisheries in the Philippines through to the late 1990s. In 1998, the species was protected nationally through the Fisheries Administrative Order No. 193. Today, the Philippines is home to over 1,950 whale sharks, making it the second-largest known whale shark population in the world.

Locally known as Butanding, Tikitiki, Tuki, or Tawiki, the whale shark has always been a part of the Filipino consciousness. Despite the country’s history of whale shark hunting, the species is seen today as an icon for tourism and is featured on the Philippine 100 peso bill.

OUR WORK

LAMAVE first started working with whale sharks to understand human-shark interactions and how these can be beneficial to both local communities and the species. We aimed to address the ecosystem-level implications of these interactions to ensure the long-term sustainability of the whale shark population.

Our whale shark conservation efforts are focused on the different sites in which they occur across the Philippines, namely Donsol, Oslob, Southern Leyte, and Palawan.

Key Areas of Research

Current population status in the Philippines as well as the broader region

Population dynamics and connectivity

Sustainability of tourism

Long-term population monitoring

Construction of a national catalog through individual identification of whale sharks

Movement patterns and distribution

We use our research findings to lobby on how we can further protect the species in both the country and across the Southeast Asian region.

Research Methodology

Our research techniques include photo-identification, satellite telemetry, focal animal follows, behavioral studies, laser & stereophotogrammetry, genetics/genomics, habitat assessment and plankton sampling, and tourism questionnaires (satisfaction, willingness to pay, improvement).

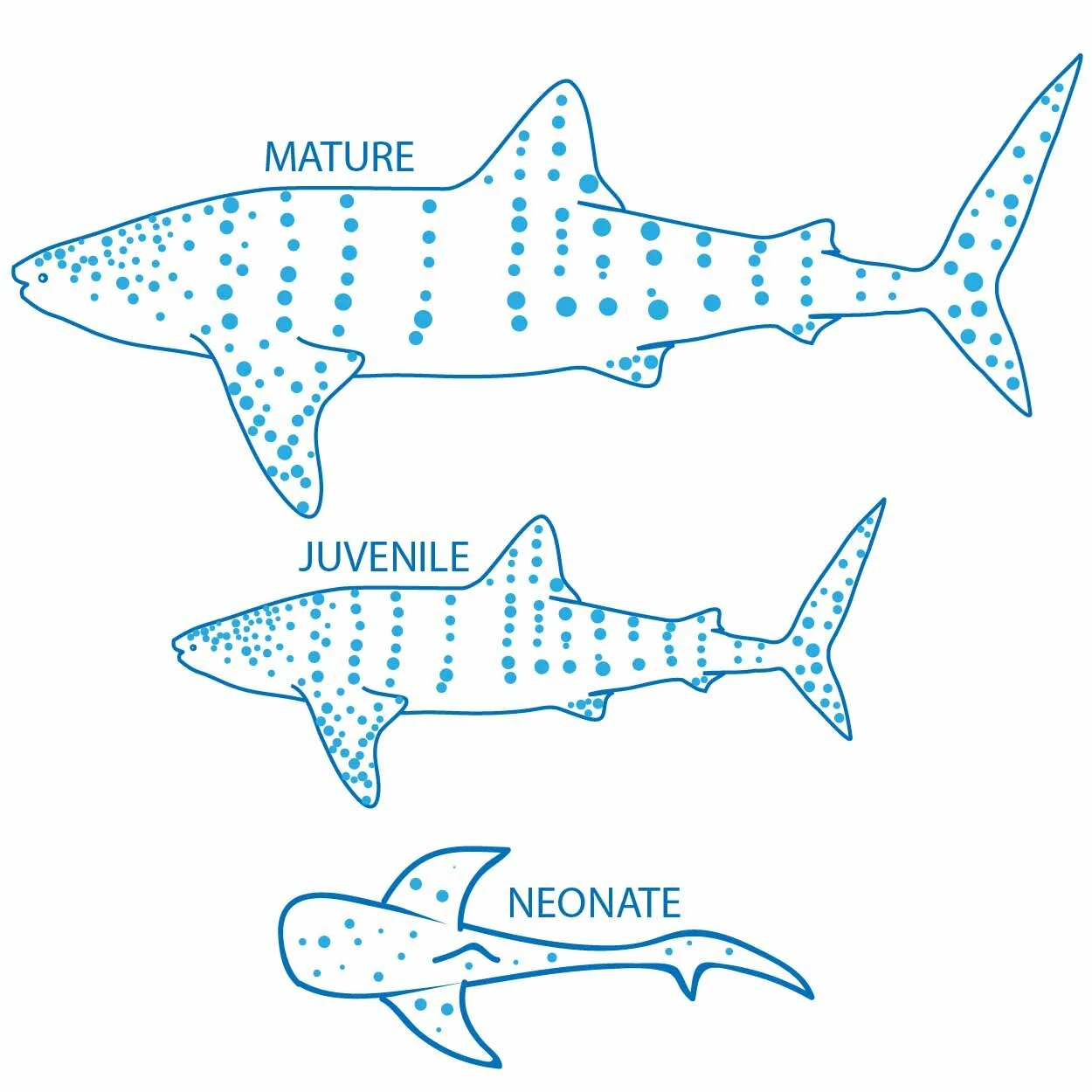

Photographic identification (photo-ID) is of particular importance to our research as we seek to understand whale shark ecology. This technique uses the unique spot pattern of each shark to identify individuals with the aid of star-mapping software. This enables us to “match” whale sharks between areas, tracking their movements.

We have employed this technique across five whale shark project sites in the Philippines. We are currently working to expand our understanding of the species’ movement as we collaborate with neighbouring countries and citizen scientists. This research is complemented by satellite tag studies, which help identify key habitats and large-scale movements between important foraging grounds, particularly on an international level.

Our team is also investigating the impact of tourism on whale sharks and their habitats to identify sustainable models that can protect the species, environment, and livelihoods of local communities.

OUR PROJECTS

Oslob Whale Shark Research & Conservation Project

Oslob, Cebu is home to the largest non-captive provisioned whale shark tourism interaction in the world. The town gained international publicity after the local government approved the feeding of whale sharks in the fishing Barangay of Tan-awan in 2012. What began as a small tourist operation has since exploded into a rapidly growing and mostly unregulated industry.

The whale shark feeding activities in Oslob have resulted in a boom in the local economy. This has come with a significant impact on the natural behavior of the whale shark, affecting its movement, residency, and local marine habitat. These effects have raised serious concerns over the sustainability of the operation.

LAMAVE in-water researchers collected daily data on the whale sharks of Oslob from March 2012 to January 2020. These eight years of work also included stakeholders’ meetings, local, regional, and national level training and workshops, and internationally published scientific studies.

Despite our best efforts, there was a perpetual unwillingness among local and regional stakeholders to shift away from unsustainable tourism and management practices. Due to this, LAMAVE decided to place our work in Oslob on hold. We will only resume this project if substantial improvement in the management of the activities is implemented.

KEY FINDINGS:

Updated as of February 21, 2020- The act of provisioning changes the whale sharks natural behaviour (diving, depth and temperature use, associated movements, and increase in vertical feeding (Schleimer et al., 2015; Araujo et al., for review);

- Anthropogenic (or human induced) scars have been observed on the body of 95% of whale sharks identified in Oslob (compared to 27% in Australia). (Penketh et al., in review)

- Prolonged residency caused by provisioning equates to less time foraging naturally. Provisioning could influence foraging success, alter distributions and lead to dependency in later life stages. (Thomson et al., 2017).

- The longer whale sharks spend in Oslob, the less their avoidance response to external stimuli such as responding to human touch and approaching boats. This process increases the risk of injury and negative fishery interaction (Schleimer et al., 2015);

- Whale shark tourism in Oslob has led to degradation of the local coral reef ecosystem as indicated by higher macroalgae cover and up to eight (8) times more coral bleaching in the interaction area than in the control site. (Wong et al., 2018)

- At least 97% of tourists get too close to the whale shark breaking the minimum distance mandated by the local Ordinance No. 091 of 2012 (Schleimer et al., 2015;Legaspi et al. for review)

- Oslob tourism is overcrowded in terms of swimmers and boats. Tourists report that seven (7) boats around a single animal is unacceptable. Alarmingly, the average number of boats in the interaction area in 2018 was 40; this is 33 more than what tourists consider acceptable (Ziegler et al., 2019)

- Oslob whale shark watching is a “Guilty Pleasure”. Two-thirds of TripAdvisor comments that mentioned ethical issues were classified as “Guilty Pleasure”, whereby the tourists were aware of the moral and ethical issues of feeding an endangered species for tourism purposes, but still chose to do the tour and recommended it to others. (Zielgler et al., 2018)

Southern Leyte Whale Shark Research & Conservation Project

A successful exploratory trip in 2012 to Panaon Island confirmed reports of whale shark presence in the area. Following this, LAMAVE established a base in nearby Pintuyan to study the population.

The whale shark season runs from November to June and is highly dictated by the southwest monsoon. Our team studied the animals while working closely with the Pintuyan local government unit, local community, and KASAKA People’s Organisation, who manage the local whale shark tourism.

In 2013, LAMAVE hosted a workshop in collaboration with Conservation Sew Mates. This was done to support the establishment of Sea Breeze Women’s Association, which is an organization composed of the wives, sisters, daughters, and mothers of the KASAKA whale shark spotters and guides. The workshop taught them how to handcraft whale shark souvenirs to supplement their livelihood.

KEY FINDINGS AND ACHIEVEMENTS:

Updated as of February 21, 2020- Over 330 individual whale sharks identified

- Found that Southern Leyte hosts the mostsustainable whale shark tourism model in the Philippines

- Matched a whale shark in Tawian with one in Southern Leyte - the first international match of a whale shark in Southeast Asia through photo-ID, covering a minimum distance of 1600 km

- Satellite tracking studies revealed connectivity of local whale sharks to other key habitats in the Bohol Sea

- Establishment of Sea Breeze Womans Association after a workshop with LAMAVE and Conservation Sew Mates.

- Discovered that the SOuthern Leyte aggregation is largely composed of juvenile male whale sharks

Donsol Whale Shark Research & Conservation Project

Donsol Bay is home to the Philippines' first whale shark tourism destination, which began in 1998 with the assistance of WWF-Philippines.

Whale sharks aggregate seasonally in these rich waters to feed between November and May. LAMAVE established a base here in 2015 to increase our understanding of this aggregation.

We have been working closely with stakeholders including the local government unit and community, Butanding Interaction Officers, the Butanding Boat Operators Association, and WWF-Philippines to assess the population status of the whale sharks and enhance the environmental sustainability of tourism operations.

KEY FINDINGS:

Updated as of March, 2020- Over 700 individual whale sharks identified in collaboration with WWF-Philippines(McCoy et al 2018)

- Identification and release of a neonate (baby) whale shark, 59cm in length, in March 2020.

- Using underwater observation and photographs the sex of 180 whale sharks was identified. 88% were male, with 53% considered sexually mature.

Palawan Whale Shark Research & Conservation Project

LAMAVE began studying whale sharks in Honda Bay, Palawan in 2016. Working with local tour operators, the Local Government Unit (LGU) of Puerto Princesa, and the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), our team conducted daily surveys between April and October to assess the population of whale sharks. This was done in line with the species’ seasonal aggregation in the bay.

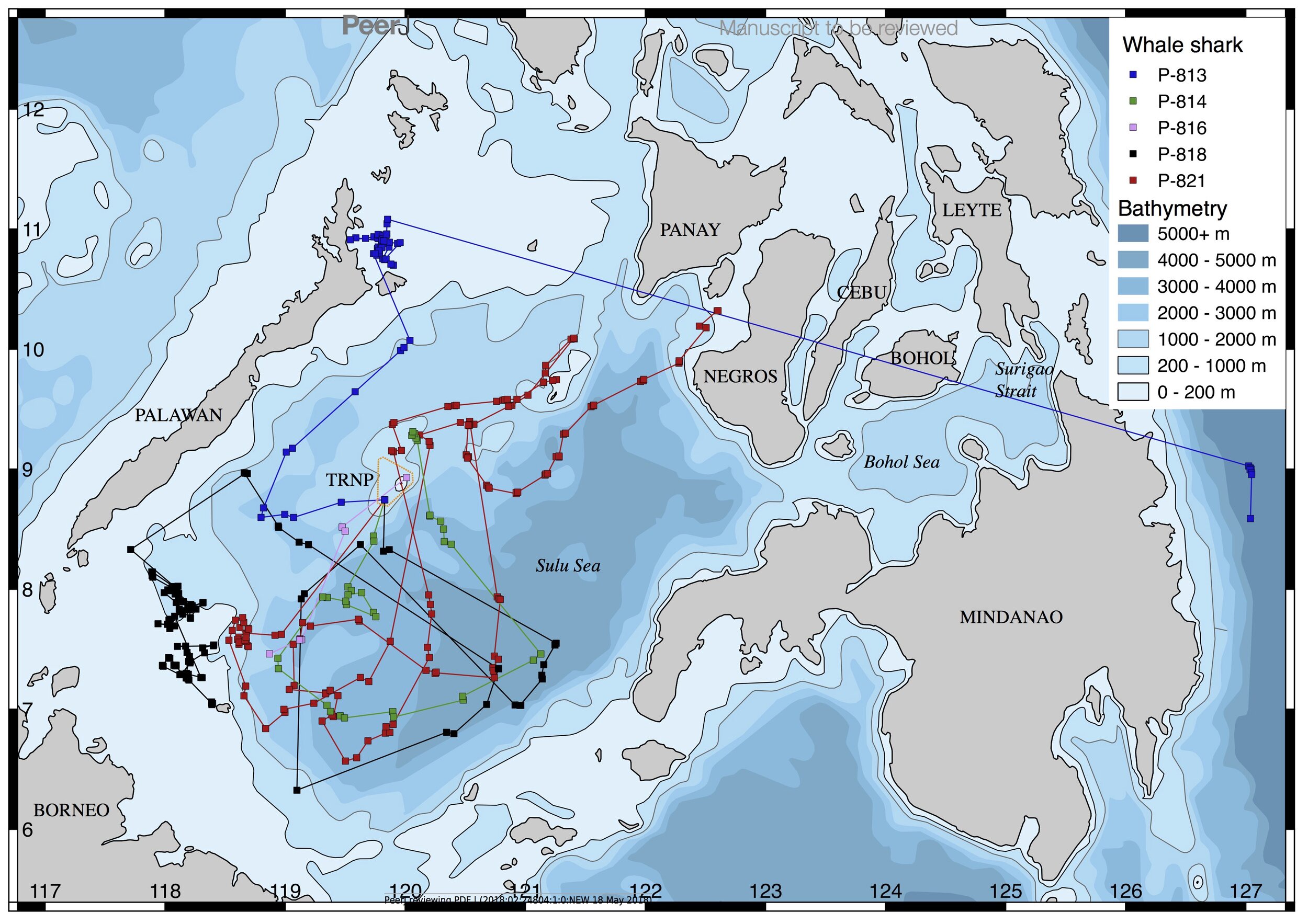

This aggregation occurs far offshore as the whale sharks are often associated with schools of mackerel tuna and other schooling fish. Individual whale sharks usually only stay in the bay for a day before continuing their movements. Satellite tags deployed on individuals encountered in the bay have revealed connectivity to different sites in the Philippines as well as internationally to Malaysia.

These whale sharks also interact with local small-scale fishers near-shore as well as medium-scale and commercial fishing vessels offshore. Many individuals exhibit signs of recent and dated fishery interactions such as scars and injuries. Understanding the potential impact of these activities on the welfare and survival of this endangered species is fundamental for its conservation.

Whale shark tourism in Honda Bay began in 2009. It remains relatively small scale with only one travel agency operating one to three large vessels at a time. However, pressure on the whale sharks and operators is expected to increase due to the growing tourism sector both in Puerto Princesa and the entire province of Palawan. As such, sustainable management and regulation of the activities is a priority for the PCSD and LGU.

KEY FINDINGS:

Updated as of February 21, 2020- Over 380 individual whale sharks identified

- Whale sharks in Honda Bay are mostly juvenile males (96.5%) ranging from 2.25 – 8.00 m in total length (mean 4.5 m).

- Whale sharks encountered in association with tuna boils and birds on the surface

- Ten whale sharks were equipped with satellite tags in 2017. Two of them were reencountered in the same area on the following year.

- Through satellite telemetry and photo-identification we identified international connectivity with Malaysia and Indonesia and nationally with Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park and the Bohol Sea.

Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park Whale Shark Research & Conservation Project

LAMAVE began studying the whale shark population in Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park (TRNP) in 2015. We worked with the Tubbataha Management Office (TMO) to collect and study citizen science submissions from the liveaboards frequenting the park.

That year, we also deployed satellite tags on whale sharks in collaboration with the TMO, the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), and the Marine Megafauna Foundation. The tags identified that whale sharks were using the atolls of Tubbataha Reefs as a navigational reference. It also revealed movements within the park as well as to various key habitats in the Bohol Sea.

KEY FINDINGS:

Updated as of March 2020- >50 individual whale sharks identified

- Satellite tags reveal connectivity with the Bohol Sea

Citizen Science

How the Public Is Helping Identify Whale Sharks and Document Their Movements

Photographic submissions of whale sharks encountered by tourists in the Philippines are helping LAMAVE with whale shark research and conservation efforts. This type of collaboration is referred to as citizen science

Area used for identification.

Whale sharks can be identified by their unique spot pattern, similar to how humans can be identified by their fingerprints. Photographs of whale sharks submitted by the public and analyzed by our team have helped document whale sharks moving between south Luzon, the Visayas, Mindanao, and Palawan.

You can contribute to this research by uploading your whale shark photographs to WildBook for Whale Sharks.

Expanding Internationally

Citizen science programmes in Sabah, Malaysia, have been actively collecting identification and presence data on whale sharks with one intriguing visitor in late 2019: a whale shark previously sighted in the south of Cebu, Philippines, was encountered at Pulau Sipadan, in Sabah, Malaysia. These findings build on current knowledge that whale sharks are moving between the Sulu and Sulawesi Seas - an area of special conservation interest with some of the world’s highest marine biodiversity.

KEY FINDINGS:

Updated as of March, 2020- Over 200 individual whale sharks identified through citizen science

- Movements documented in Southern Luzon, the Visayas, Mindanao and Palawan

- Photo-ID match revealing connectivity between Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia

OUR IMPACT

Impact & Output

>1,950 whale sharks identified in the Philippines

Mature, Juvenile and Neonate whale sharks discovered.

39 tagged whale sharks (satellite tags, Time Depth Recorders, 3D tags)

Connectivity to Taiwan, Indonesia and Malaysia

Second largest known population of whale sharks identified worldwide

Advisor to the Philippines for its successful nomination of the whale shark to Annex 1 of Conservation Migratory Species (CMS)

15 scientific publications outlining findings from research projects

Advised and supported the municipalities of Pinutyan and Liloan to draft and pass local ordinances to regulate and manage the tourism interactions in Sogod Bay.

Updated April 2020

Publications

Getting the most out of citizen science for endangered species such as whale shark. Araujo, G., Ismail, A.R., McCann, C., McCann, D., Legaspi, C.G., Snow, S., Labaja, J., Manjaji-Matsumoto, M., & Ponzo, A. Journal of Fish Biology 2020

Measuring perceived crowding in the marine environment: Perspectives from a mass tourism ‘swim-with’ whale shark site in the Philippines. Ziegler, J. A., Araujo, G., Labaja, J., Legaspi, C., Snow, S., Ponzo, A., Rollins, R., & Dearden, P. Tourism in Marine Environments, Volume 14, Number 4, 2019, pp. 211-230(20)

Observations of microzooplankton in the vicinity of whale shark Rhincodon typus aggregation sites in Oslob, Cebu and Pintuyan, S. Leyte, Philippines. Yap-Dejeto L., Cera, A., Labaja, J., Palermo, J. D., Ponzo, A., & Araujo, G. Philippines Journal of Natural Sciences. 22:61-77

Photo-ID and telemetry highlight a global whale shark hotspot in Palawan, Philippines. Araujo, G., Agustines, A., Tracey, B., Snow, S., Labaja, J., & Ponzo, A. Scientific Reports 2019

Whale shark tourism: impacts on coral reefs in the Philippines. Wong, C.W.M., Conti-Jerpe, I., Raymundo, L.J., Dingle, C., Araujo, G., Ponzo, A., & Baker, D.M. Environmental Management (2018)

Long-term photo-identification reveals the population dynamics and strong site fidelity of adult whale sharks to the coastal waters of Donsol, Philippines. McCoy, E., Burce, R., David, D., Aca, E.Q., Hardy, J., Labaja, J., Snow, S.J., Ponzo, A., & Araujo, G. (2018) Frontiers Marine Science. 5:271.

Satellite tracking of juvenile whale sharks in the Sulu and Bohol Seas, Philippines. Araujo, G., Rohner, C. A., Labaja, J., Conales, S. J., Snow, S.J., Murray, R., Pierce, S.J., & Ponzo, A. PeerJ 6:e5231; (2018)

A guilty pleasure: Tourist perspectives on the ethics of feeding whale sharks in Oslob, Philippines. Ziegler, J.A., Silberg, J.N., Araujo, G., Labaja, J., Ponzo, A., Rollins, R., & Dearden, P. Tourism Management 68 (2018) 264-274

Applying the precautionary principle when feeding an endangered species for marine tourism, Ziegler, J.A, Silberg, J.N, Araujo, G., Labaja, J., Ponzo, A., Rollins, R., Dearden, P. Tourism Management 72 (2019) 155-158

Using long-term integrated research programs to improve whale shark tourism at Oslob, Philippines. Ziegler, J.A, Silberg, J.N., Araujo, G., Labaja, J., Ponzo, A., Rollins, R., & Dearden, P. Tourism Management 74 (2019) 297-299

iDNA at sea: recovery of whale shark (Rhincodon typus) mitochondrial DNA sequences from the whale shark copepod (Pandarus rhincodonicus) confirms global population structure. Meekan, M., Austin, C.M., Tan, M.H., Wei, N.V., Miller, A., Pierce, S.J., Rowat, D., Stevens, G., Davies, T.K., Ponzo, A., & Gan, H.M. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2017

Undersea constellations: the gobal biology of an Endangered marine megavertebrate further informed through Citizen Science. Norman, B.M., Holmberg, J.A., Arzoumanian, Z., Reynolds, S.D., Wilson, R.P., Rob, D., Pierce, S.J., Gleiss, A.C., de la Parra, R., Galvan, B., Ramirez-Macias, D., Robinson, D., Fox, S., Graham, R., Rowat, D., Potenski, M., Levine, M., Mckinney, J.A., Hoffmayer, E., Dove, A.D.M., Hueter, R., Ponzo, A., Araujo, G., Aca, E., David, D., Rees, R., Duncan, A., Rohner, C.A., Prebble, C.E.M., Hearn, A., Acuna, D., Berumen, M.L., Vázquez, A., Green, J., Bach, S.S., Schmidt, J.V., Beatty, S.J., & Morgan, D.L. BioScience, 2017

Feeding the world’s largest fish: highly variable whale shark residency patterns at a provisioning site in the Philippines. Thomson J.A., Araujo, G., Labaja, J., McCoy, E., Murray, R., & Ponzo, A. Royal Society Open Science, 2017

Assessing the impacts of tourism on the world's largest fish Rhincodon typus at Panaon Island, Southern Leyte, Philippines. Araujo G, Vivier F, Labaja JJ, Hartley D, & Ponzo A. Aquatic Conservation: Marine Freshwater Ecosystems. 2017;00:1–9.

Population structure, residency patterns and movements of whale sharks in Southern Leyte, Philippines: results from dedicated photo-ID and citizen science. Araujo, G., Snow, S.J., So, C.L., Labaja, M.J.J., Murray, R., Colucci, A., & Ponzo, A.; Aquatic Conservation, 2016.

Learning from a provisioning site: code of conduct compliance and behaviour of whale sharks in Oslob, Cebu, Philippines. Schleimer, A., Araujo, G., Penketh, L., Heath, A., McCoy, E., Labaja, J., Lucey, A., & Ponzo, A.; Peer J, 2015

Population structure and residency patterns of whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, at a provisioning site in Cebu, Philippines. Araujo, G., Lucey, A., Labaja, M.J.J., So, C.L., Snow, S.J., & Ponzo, A.; Peer J, 2014.

Humans of Typhoon Odette - Andy Leonor

“We lost our livelihoods again because of Super Typhoon Odette. Nawalan kami ng hanapbuhay dahil kay Odette. I used to work in tourism here in Puerto Princesa but my job was affected by the pandemic. I looked for an alternative source to be able to survive, but then the typhoon came. It has been really difficult. I don’t know what to do anymore. So na Nahihirapan na ako. Hindi ko na alam kung anong gagawin ko. I don’t know how to start over.”